Westonbirt, in Gloucestershire, is registered at Grade I. Described in the Register entry as nineteenth-century ‘pleasure grounds, park, and arboretum… associated with one of the most expensive of the Victorian country houses’, it is now in divided ownership, but its most significant components – now the gardens at Westonbirt School, and the National Arboretum – can still be visited.

History

Much of the history of the site is outlined here, and in the Register entry. The Holford family had been at Westonbirt since the 1660s. A sixteenth-century house on the site of what are now the garden terraces had a lawn, and parkland (the park was created by 1674, and divided into two parks by 1700). This house was demolished in 1818 by George Holford, and replaced in 1823 by a Regency Gothic house a little to the north, and the associated gardens, including the Church Terrace immediately to the south of the house (now the oldest architectural feature in the gardens, with a yew in front of the house the oldest tree), and an octagonal kitchen garden to the east (now the site of the Kitchen and Italian Gardens).

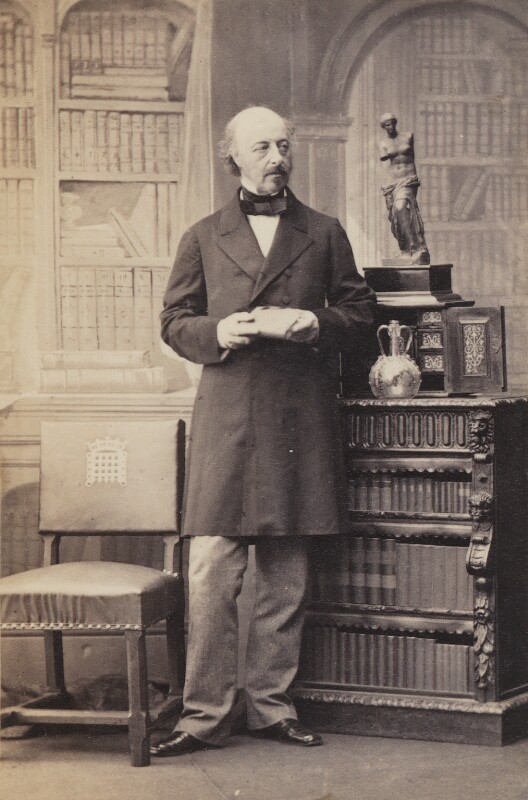

Robert Stayner Holford, George’s son, expressed an early interest in plants and design, and started to create an arboretum in 1829. On inheriting the property in 1839 (and having recently also benefited from a sizeable inheritance from his uncle), Robert expanded the park, and laid out the Italianate gardens. In the 1860s, Robert demolished the house built by his father, and replaced it on the same site with the current Westonbirt House. It is now listed at Grade I, and, as noted in the list entry, was designed by Lewis Vulliamy ‘in the style of Elizabethan prodigy houses’ – strongly influenced by the sixteenth-century Wollaton Hall in Nottinghamshire. Whilst occupied from 1872, the house was not completed until 1921.

It is worth noting that Robert Stayner Holford’s grand plan had a wider impact on the area. As outlined in the Register entry, the extension of the park in the 1840s:

… involved abandoning the old approach road in place of the two drives, completed by c 1853; demolishing the eastern part of Westonbirt village which stood south-west of the church and rehousing its inhabitants in the present settlement c 300m to the west in cottages (outside the registered area) probably by Lewis Vulliamy completed by c 1856; and finally, closing the Easton Grey road across the park c 1868.

The Holford Trust history suggests that the village had comprised ‘10 cottages, a rectory and a farm house’. Its relocation also required the ‘diversion and culverting of the village brook’, and, to add insult to injury, the ‘construction of a sunken pathway (with an iron footbridge over) which allowed the villagers to access the parish church without disturbing Robert Holford’s privacy’.

Robert’s son, Sir George Holford, inherited in 1892: ‘a soldier and courtier, he was an Equerry to King Edward VII and regularly hosted royal visitors at Westonbirt’. Sharing his father’s interest in gardening – and with a particular interest in orchids and amaryllis – from the 1880s, he took on much of the work to develop the estate, not least in the arboretum. On Sir George’s death in 1926, the property passed to his nephew, Lord Morley, who sold the house and much of the estate to the Martyrs’ Memorial and Church of England Trust, which opened Westonbirt School in 1928. Lord Morley retained and continued to add to the arboretum, but the wider site was reunited whilst requisitioned by the Air Ministry during World War II. On Lord Morley’s death in the 1950s, the arboretum passed to the Crown in lieu of death duties, and remains in the ownership of what is now Forestry England.

The Holfords of Westonbirt Trust was created in 2006 to ‘enable the long term conservation of the house and gardens and to make them accessible to a wider audience’, and has ‘delivered conservation projects totalling more than £1 million’, including the Westonbirt Revealed project (completed in 2021), which repaired and refurbished various historic features within the garden.

The Gardens

The gardens at Westonbirt were primarily developed between 1830 and 1860 by Robert Stayner Holford, and reflect William Sawrey Gilpin’s ‘picturesque’ style of landscaping. As noted on the Holford Trust website, Gilpin’s influence on Robert Stayner Holford’s work:

… is reflected at Westonbirt in the combination of the formal terraces and lawns immediately surrounding the house which gradually give way to informal areas with carefully placed specimen trees.

The gardens were largely created around the 1823 house, though the latter stages of their development were very much informed by the plan to build the much larger house (the Register entry confirms that ‘the gardens were essentially complete before the House was rebuilt in 1863’).

The 1840s saw, first, the removal of the kitchen garden to the east of the House, and the creation of the Italian Garden, on the site of the earlier octagonal flower garden, as well as the nearby Sunken Garden, Mercury Pond and Bishop’s Seat, all to the east of the house. The Italian Garden is listed at Grade II*. A large rectangular space, it has pavilions at the two northern corners and stone arches at the southern ones. There is a heated brick wall to the north, with a Camellia House at its centre (a remnant of the Holfords’ many ornamental glasshouses): the stone columns flanking the Camellia House’s entrance were the chimneys for the heated wall. To the south of the Italian Garden is an extraordinary glass-sided pond, with fountains. The statue of Mercury in the stone basin pond in the adjoining Sunken Garden – formerly known as the Circular Garden – is listed (Grade II), as is the stone shelter with seat to the east (also Grade II).

The Long (or Lower) Terrace is the second of three paths radiating from the axial path centred on the house, all running parallel to the Upper (or South) Terrace along the house front (the Upper Terrace is included within the list entry for the house, though the sundial in its eastern half is listed separately, at Grade II. The ‘ornamental terraced steps and walls’ of the other terraces are listed in their own right, also at Grade II). Beneath the Church Terrace, and similarly terminated to the west with a decorative stone seat, the Long Terrace was created in 1846, with lawn and specimen trees to either side.

Between 1847 and 1852, the park was enlarged as described above, and roads realigned. These changes were followed by the construction of new entrance lodges. Pickards Lodge and gate piers (Grade II), to the east of the house, were built in 1848, almost certainly by Lewis Vulliamy. The North entrance gate, screen walls and lodges were built in 1853 (also listed at Grade II, and are also believed to have been designed by Lewis Vulliamy). Westonbirt village was relocated and rebuilt between 1854 and 1856.

The village relocation enabled the creation of the gardens to the west of the house and church. The Register entry confirms that these were ‘part of the area occupied until the 1850s by Westonbirt village’; the lake there (which dates from the 1860s, and contains a concrete lining, and rock cascade, both by James Pulham & Son) is an extension of the former village pond (the golf course to the south west of the house – owned by the school – was created on the site of the old village by 1936). In the southern portion of this part of the grounds is the ‘Amphitheatre’, a tiered lawn created by the school in the 1920s for performances but no longer used.

The 1860s saw the construction of another lodge, again to the east of the house. East Lodge is listed at Grade II, and, again, is by Lewis Vulliamy, as is the ha-ha constructed between 1863 and 1870, marking the southern boundary (Grade II). In the 1870s, James Pulham & Son constructed a grotto and rockery to the north of the lake using both limestone and artificial rocks, and replacing a rockery from the 1840s.

In the 1880s, the gardens were extended to the south, and the third of the parallel terraces constructed, below the Long Terrace and the site of the sixteenth-century house. The Fountain Pond was relocated from the former termination of the axis on the Long Terrace to become the end point of the extended axial path.

The gardens (and house) are opened to the public on select days each year, and the excellent tours must be booked in advance.

The Arboretum

The website for Westonbirt Arboretum describes it as ‘one of the most beautiful and important plant collections in the world’:

With 15,000 specimens, and 2,500 species of tree from all over the globe, the arboretum plays a vital part in research and conservation, as well as being a stunningly beautiful place to visit.

The arboretum was created on what had previously been common downland. Robert Stayner Holford’s interest in plants, and his wealth, were such that he was able to finance plant-hunting expeditions, and then accommodate the results in his arboretum – many of which survive. A helpful timeline notes that the first recorded plantings took place in 1829, in the eastern portion of the site (a map of the 240-hectare arboretum may be viewed here), and, further, that planting was guided by aesthetics – reflecting the Picturesque movement – rather than by species or country of origin: ‘the result is a botanical collection that is famed worldwide today not only for its astonishing diversity, but also its breathtaking beauty’.

The arboretum was extended in 1840 with the purchase of Silk Wood, to the west, beyond the ‘Downs’ (a shallow valley) where existing woodland was supplemented with new species, including Douglas fir and lime plantations. The bulk of the planting in the arboretum took place between 1852 and 1881. The Register entry notes that radiating rides were added to what is now known as the ‘Old Arboretum’ in 1855, aligned on Westonbirt House, currently named Jackson Avenue, Holford Ride, and Morley Ride (Jackson Avenue was originally a double avenue with cedar and lime trees on the inside, and beech and yew on the outside. Tulip trees replaced some of the cedars around 1910, and many of the beech trees were lost in the summer of 1976). Acer Glade was added between 1850 and 1870, and drives were subsequently added to Silk Wood, too (Waste, Broad, and Willesley Drives).

The then Forestry Commission took on the site in 1956, and it opened to the public in 1961. A Japanese Maple Collection was begun in Silk Wood in 1982 – now one of five national collections on the site, with around 300 different types of cultivar (the other national collections are maples (‘an important part of the arboretum since… the 1870s’), bladdernut, lime, and walnut). Westonbirt is also home to 140 champion trees: the largest of their species within the British Isles. They are recognisable not just by their size but by their blue (rather than black) labels.

The arboretum is open every day (other than Christmas day). Pre-booking is required at some times of year, and it’s always worth checking if there are events on.

Conclusion

Visiting both the house and the arboretum on the same day takes some forethought, but can be done (my own visits took place three years apart). The ownership of the registered landscape is more fragmented than this account of its two most significant components might suggest, but its original form remains remarkably legible, all things considered. As the arboretum’s website notes, Robert Stayner Holford’s house, gardens and arboretum at Westonbirt are indeed ‘a lasting testament to his taste and wealth’.