In the year of the fortieth anniversary of the power to create the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England, it is a particular delight to be able to welcome a new gardens-related provision, courtesy of the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act 2023, which received Royal Assent on 26 October 2023. Section 102 of the Act requires local planning authorities to have special regard to the desirability of preserving or enhancing a park or garden or its setting when they are considering granting planning permission. This is the latest development in the slow but steady increase in protection for historic parks and gardens: this post looks at the most significant to date (with a focus on planning rather than financial measures, as the planning system is the primary mechanism for the protection of historic parks and gardens).

1983: Power to Create the Register

The power to create the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England was introduced by the National Heritage Act 1983. It took some time to get to this point (the tortuous process is outlined here and here; the way in which the Register is now used is addressed here), but the result was a permissive power for English Heritage (now Historic England) to create a register of ‘gardens and other land situated in England and appearing to them to be of special historic interest’. Initially, this was all that happened; as outlined during the passage of the legislation through Parliament:

The object of the register is not to introduce a new set of controls, but to bring forcefully to the attention of planners and public bodies, who are planning roads and other things, the value of these gardens and landscapes.

The first Register entries were made in 1984, and, by October 2023, 1,704 historic parks and gardens had been designated.

1987: First Planning Policy Reference

Merely bringing parks and gardens ‘forcefully to the attention of planners and public bodies’ was not enough, however, especially as the wider planning context was particularly weak by the time the Register emerged, with a presumption in favour of development in force.

Circular 8/87: Historic Buildings and Conservation Areas – Policy and Procedure was the first policy statement relating to parks and gardens to be produced after the introduction of the Register in 1983. It was not the most extensive or robust statement, but it was an important first step, clarifying the purpose of the Register:

The register, which has no statutory force, lists and grades gardens which still retain their special historic interest. Its purpose is to record their existence so that highway and planning authorities, and developers, know that they should try to safeguard them when planning new road schemes and new development generally.

1994: Development of Planning Policy

Circular 8/87 was superseded in 1994 by Planning Policy Guidance Note 15: Planning and the Historic Environment (PPG15), which made more extensive – and more positive – reference to historic parks and gardens. For one thing, PPG15 formally linked the production of the Register to the planning system for the first time. It also stated unequivocally that local planning authorities ‘should protect registered parks and gardens in preparing development plans and in determining planning applications’: whilst local plan policy references to historic parks and gardens remained limited, this was a very important development.

PPG15 also confirmed that ‘the effect of proposed development on a registered park or garden… is a material consideration’ (a material consideration being something that will be taken into account when a planning decision is made). This was an important step in a planning system which by now gave greater weight to material considerations, and further strengthened the role of the Register in planning matters.

Further contributions made by PPG15 included an explanation of the grading system used in the Register (discussed further here), the suggestion that conservation area designation could be suitable for historic parks or gardens, and reference to the protection of trees.

1995: Statutory Consultation Requirement

The next development was the introduction of a requirement for statutory consultation on planning applications for ‘development likely to affect’ registered parks and gardens. This important new provision emerged after the Garden History Society (now Gardens Trust) and others pressed the National Heritage Select Committee for it; the Committee’s subsequent recommendation prompted the requisite action by Government.

The original provision was first made in a circular letter from the Department of the Environment, covering the Town and Country Planning (Consultation with the Garden History Society) Direction 1995; the Direction was then reissued in Circular 9/95: General Development Order Consolidation 1995, which also explained the English Heritage consultation requirement (itself introduced via the Town and Country Planning (General Development Procedure) Order 1995. The consultation requirements are now set out together in the Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015. The result is that local planning authorities considering planning applications for development likely to affect registered parks and gardens are required to consult as follows:

- Historic England (the Government’s statutory adviser on the historic environment in England) in relation to those classified as Grade I and II*

- The Gardens Trust in relation to registered parks and gardens of all grades (thereby making the Gardens Trust a statutory consultee in the planning system).

The key benefit of this consultation requirement is ensuring that local planning authorities receive specialist input to inform their decision-making – assuming, of course, that the authority in question properly interprets the term ‘affects’ (development affecting a registered park or garden can be within or outside the defined boundary of the designated landscape). Nevertheless, this was a key development in the protection of historic parks and gardens. This was indirectly acknowledged in the Town and Country Planning (General Development Procedure) Order 1995, which described the requirement to consult what is now Historic England as the ‘main change made by the Order’: notification requirements were now broadly in line with those for listed buildings.

2010: Further Development of Planning Policy

It was some time before the next development, but, when it finally emerged, it was another important one. Parks and gardens had first been mentioned meaningfully in national planning policy in 1994, but the provisions in PPG15 were to be superseded in 2010, with the publication of Planning Policy Statement 5: Planning for the Historic Environment (PPS5).

PPS5 changed the conservation landscape in a number of ways. The first was its introduction of a significance-based approach to English planning policy – significance being ‘the value of a heritage asset to this and future generations because of its heritage interest’. The level of protection offered rested on the nature of that interest, and its relative importance.

The second key change in policy was the parity created for a range of heritage designations, in policy terms at least (the different statutory provisions underpinning listed buildings, conservation areas and scheduled monuments remained in force): registered parks and gardens became subject to the same broad protection as world heritage sites and listed buildings, as ‘designated heritage assets’. The overall result was strong policy support for the conservation of historic parks and gardens, and enhanced visibility:

There should be a presumption in favour of the conservation of designated heritage assets and the more significant the designated heritage asset, the greater the presumption in favour of its conservation should be…. Substantial harm to or loss of a grade II… park or garden should be exceptional. Substantial harm to or loss of… grade I and II* registered parks and gardens… should be wholly exceptional.

PPS5 also extended a degree of protection to non-registered parks and gardens for the first time: ‘the effect of an application on the significance of [a non-designated] heritage asset or its setting is a material consideration in determining the application’.

Whilst the presumption in favour of conservation has now been lost (subsumed into a single presumption in favour of sustainable development), subsequent iterations of national planning policy – set out in the National Planning Policy Framework – have retained this overall policy approach.

2023: Statutory Duty

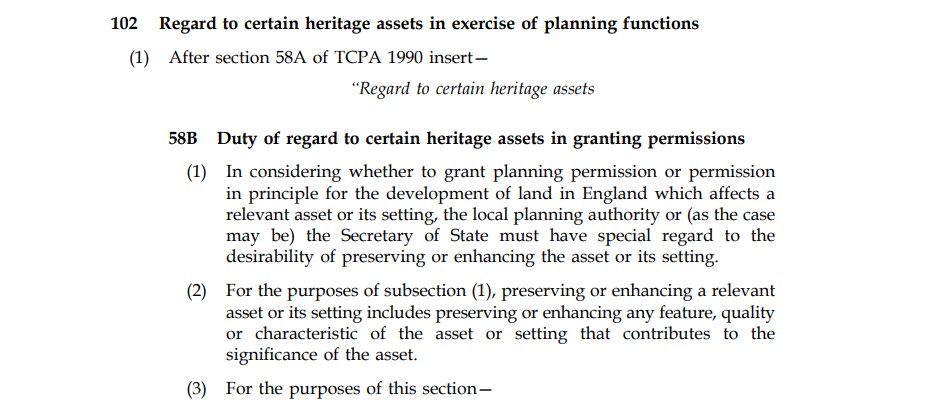

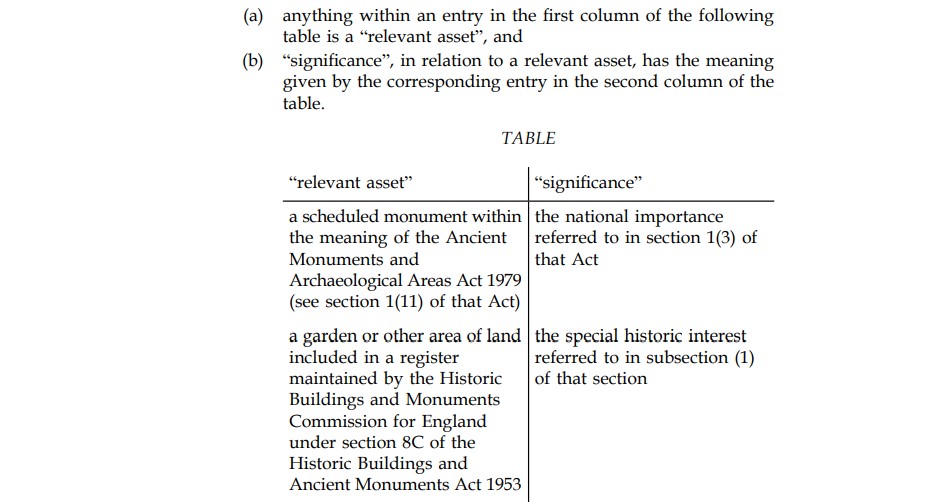

The Levelling Up and Regeneration Act 2023 introduces a number of planning reforms, but the provision of most interest in the current context is section 102 (‘Regard to certain heritage assets in exercise of planning functions’), which introduces a form of statutory parity for all types of designated heritage asset, to supplement the existing policy parity.

The statutory parity comes via an extension of the previous requirement for local planning authorities making decisions on applications on listed buildings to have special regard to the desirability of preserving the buildings or their setting, or any features of special architectural or historic interest they possess (preservation in this context means not harming the interest in the building, as opposed to keeping it utterly unchanged). The new duty requires those considering whether to grant planning permission for development which affects a ‘relevant asset’ or its setting (i.e., local planning authorities or the Secretary of State, in England) to have ‘special regard to the desirability of preserving or enhancing the asset or its setting’.

Preserving or enhancing a relevant asset or its setting includes ‘preserving or enhancing any feature, quality or characteristic of the asset or setting that contributes to the significance of the asset’. Registered parks and gardens are identified as ‘relevant assets’, and the ‘significance’ to be considered is their special historic interest. At the risk of labouring the point, this means that, when they are considering granting planning permission for the development of land in England which affects a registered park or garden, or its setting, local planning authorities or the Secretary of State are required to have special regard to the desirability of preserving or enhancing that park or garden or its setting. This includes preserving or enhancing any feature, quality or characteristic of the park or garden, or its setting, that contributes to the park or garden’s special historic interest. All of which should force more careful consideration of proposals, and improved conservation of historic parks and gardens.

This is an important additional layer of protection. In relation to the existing listed building duty, for instance, the Courts have confirmed that decision makers must give ‘considerable importance and weight’ to the desirability of preserving the setting of listed buildings when balancing harm against any likely public benefits or other material considerations weighing in favour of a proposal. Not demonstrably doing so has led to some planning consents being quashed, and parks and gardens will now benefit from this extra requirement and associated scrutiny.

It is also worth noting that this provision has been introduced within a wider context of deregulation: the addition of a statutory duty is big news. It is probably the biggest milestone in the conservation of historic parks and gardens since the power to create the Register was introduced in 1983. It is not quite the statutory duty that the then Garden History Society considered back in 1993, which was ‘the introduction of a statutory provision imposing a duty on local authorities to preserve or enhance the character or appearance of registered gardens’ (in its Report of the Working Party on Statutory Protection for Historic Parks and Gardens), but it is certainly something to be celebrated.

Conclusion

The various milestones in the evolution of the protection of historic parks and gardens have taken a variety of forms: three were introduced through policy, one through secondary legislation, and two through primary legislation. What they all have in common is a degree of preparedness: interested parties (notably the Garden History Society/Gardens Trust) had considered the issues, formulated possible solutions, and kept the profile of historic park and gardens high. Thus, when opportunities arose, they could be seized. Active efforts in support of park and garden conservation have undoubtedly also helped: it is very clear that these are cherished assets, deserving of further protections, and that these protections will be well utilised.

Are the various protections all that could be wished? Yes and no. As discussed elsewhere, the power to create the Register was a somewhat diluted provision, compared to what was put forward during its passage through Parliament. But, over the years, the majority of the original proposals were implemented through other vehicles. There are arguably still some items on the wish-list, though. The most long-lived and high profile is probably the ongoing debate as to the merit, form, and likelihood of a dedicated consent regime for historic parks and gardens. A reduction in permitted development rights would also reduce the various potentially damaging activities which can currently take place in historic parks and gardens without the consideration and control that a need for planning permission brings. A requirement for consultation on proposals which do need planning permission is already in place, but, although caselaw suggests that a failure to observe this requirement can result in any resulting consents being quashed, compliance remains patchy, and wider efforts to ensure the requisite consultation takes place are still needed.

So there remains work to be done. But, for now, it is worth sitting back and reflecting on the fact that, although historic parks and gardens were only formally recognised as part of the historic environment in England over thirty years after historic buildings were first protected by legislation, and a century after ancient monuments, they now have parity in planning policy, and in the statutory duty to have special regard: this is an important moment in the conservation of these splendid heritage assets.

Thank you Victoria for this lucid analysis. I wish S. 102 had been in operation five years ago; Heigham Park in Norwich might well have retained its historic grass tennis courts.

LikeLike

Thank you, Lesley – glad it was of interest. In terms of what might have been, it’s hard to know, isn’t it (and hard to think about losses that might have been avoided)? The existing duty in respect of listed buildings doesn’t always save the day, but has nonetheless proved very useful – here’s hoping section 102 has the same effect for parks and gardens in future!

LikeLike