Every now and then I have a rummage through early conservation legislation. During a recent return to the Ancient Monuments Protection Act, 1882 (‘an Act for the better protection of Ancient Monuments’), I noticed an intriguing reference to married women in section 9 (‘Description of owners for purposes of Act’): this post presents the findings from my subsequent investigations.

Ancient Monuments Protection Act, 1882

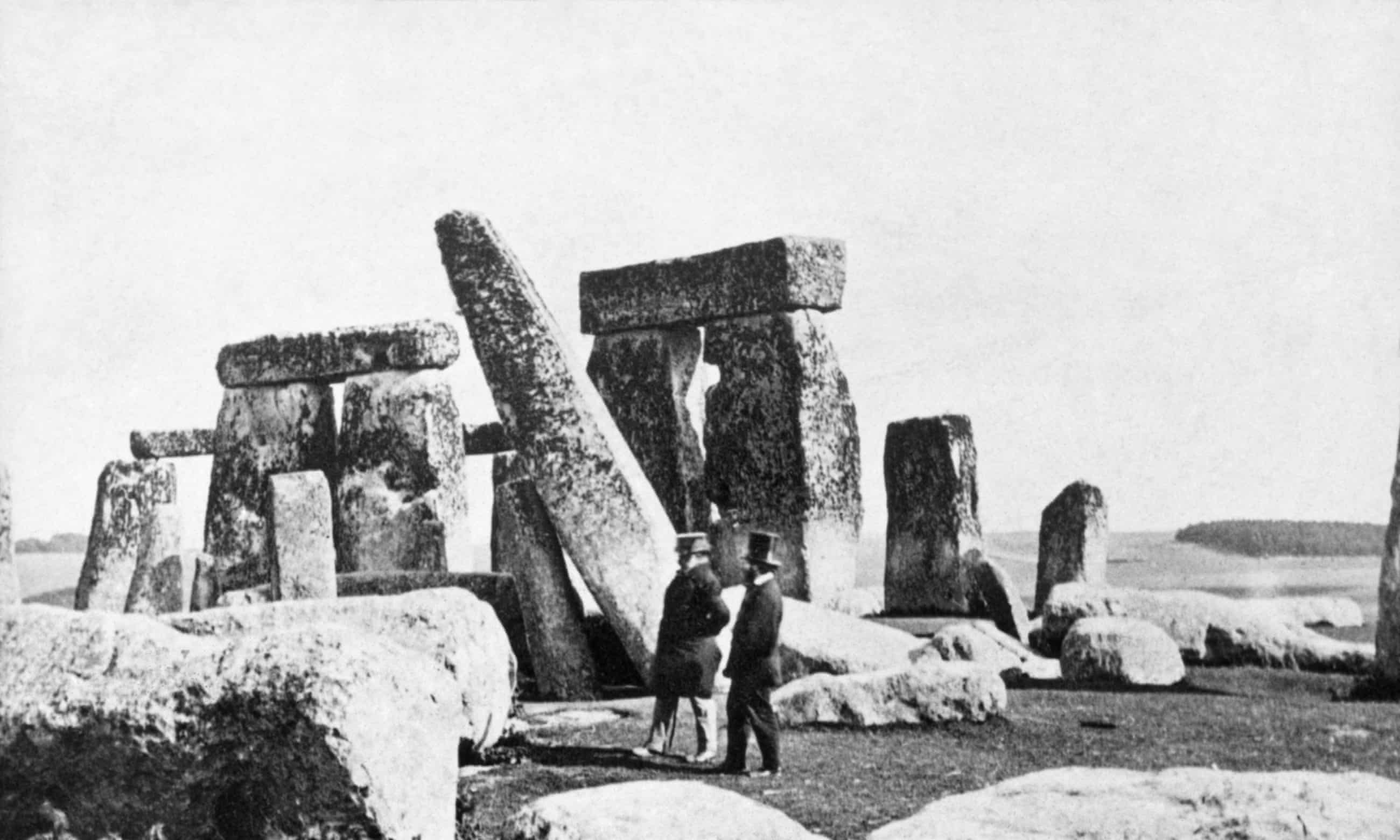

The origin of the Act, and the later application of the provisions it introduced to the protection of parks and gardens, are addressed in an earlier post. In essence, the Act introduced the scheduling of monuments, and was the first piece of legislation for the protection of the historic environment in England. A Bill was first introduced in 1873, by Sir John Lubbock (later Lord Avebury), but it took a number of compromises, seven further introductions, and nearly a decade before the provisions finally reached the statute book, on 18 August, 1882 (Sir John Lubbock noted that, ‘while it was, no doubt, a step in the right direction… he could not himself hope that it would prove altogether effectual’). Whilst the Act was relatively weak in relation to the protection of monuments, it did introduce ‘the Schedule’: ancient monuments were defined in the Act as the ‘monuments listed in the Schedule hereto’ (just 26 in England, compared to around 20,000 today: ‘though the list had been carefully drawn up, and was of a thoroughly typical character, it had no pretensions to completeness’), and are still referred to as scheduled monuments.

There are eleven sections in the 1882 Act, and one schedule (compared to sixty-five sections in the current legislation, the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979, and five schedules). Section 1 of the 1882 Act confirms the Act’s everyday title. Section 2 enables the owner of an ancient monument to appoint the Commissioners of Works as the guardians of the monument. Until advised to the contrary by any subsequent owners not bound by this (and anyone ‘deriving title… from, through, or under any owner who has constituted the Commissioners of Works the guardians… shall be bound’ by it), the Commissioners of Works shall ‘maintain such monument’ with access ‘at all reasonable times… for the purpose of inspecting it, and of bringing such materials and doing such acts and things as may be required for the maintenance thereof’. Section 3 enables the Commissioners of Works to purchase ancient monuments, whilst section 4 creates the power to ‘give, devise or bequeath’ ancient monuments to them, and for them to accept.

Section 5 makes provision for the appointment of inspectors of ancient monuments, ‘whose duty it shall be to report to the Commissioners of Works on the condition of such monuments, and on the best mode of preserving the same’. Section 6 introduces the penalties for ‘any person’ injuring or defacing an ancient monument, namely a penalty of up to five pounds, and ‘such sum as the court may think just for the purpose of repairing any damage’, or imprisonment with or without hard labour for up to a month. In contrast, the owner of an ancient monument ‘shall not be punishable… in respect of any act which he may do to such monument’, unless the Commissioners of Works have been constituted guardians of the monument. Section 7 relates to the recovery of penalties. Section 8 provides a ‘description of Commissioners of Works, and law as to disposition in their favour’.

Section 9 relates to the description of owners for the purposes of the Act, which we shall come back to. Section 10 enables the monarch to ‘declare that any monument of a like character to the monuments described in the Schedule… shall be deemed to be an ancient monument to which this Act applies’. Section 11 defines various terms, including:

- ‘Ancient monuments to which this Act applies’: the monuments described in the Schedule and ‘any other monuments of a like character of which the Commissioners of Works at the request of the owners thereof may consent to become guardians’

- ‘Ancient monument’: ‘includes the site of such monument and such portion of land adjoining the same as may be required to fence, cover in, or otherwise preserve from injury the monument standing on such site, also the means of access to such monument’.

Many of these provisions survive in some form in the current legislation, though the provision for hard labour is noticeably absent.

‘A Minor, or of Unsound Mind, or a Married Woman’

Section 9 addresses the description of owners for the purposes of the Act. This all relates to the rents and profits from various forms of property holdings, for ‘any person entitled for his own benefit, at law or in equity’, or ‘any body corporate, any corporation sole, any trustees for charities, and any commissioners or trustees for ecclesiastical, collegiate, or other public purposes’. The reference that originally caught my eye was this one:

Where any owner as herein-before defined is a minor, or of unsound mind, or a married woman, the guardian, committee, or husband, as the case may be, of such owner, shall be the owner within the meaning of this Act; subject to this proviso, that a married woman entitled for her separate use, and not restrained from anticipation, shall for the purposes of this Act be treated as if she were not married.

The grouping of the references to minors, those of unsound mind, and married women – as well as the order in which they are listed – are telling in themselves. The context to the initial reference to the husband of a married woman being the owner of an ancient monument is that, from the thirteenth century until 1870, as outlined here, all money and property held by women became the property of their husband on marriage. Whilst a single or widowed woman was a ‘feme sole’, with the right to own property and enter into contracts, a married woman was a ‘feme covert’, i.e. her legal existence was effectively merged with her husband’s. There were some exceptions to this, requiring forethought and access to legal advice. As outlined here:

… fathers often provided [daughters] with dowries or worked into a prenuptial agreement pin money, the estate which the wife was to possess for her sole and separate use not subject to the control of her husband, to provide her with an income separate from his.

Additionally, property acquired by a wife after marriage could be specified to be for her own separate use, involving the use of trustees:

… who would legally hold the property ‘to her use’, and for which she would be the equitable and beneficial owner’. The wife would then receive the benefits of the property through her control of the trustees and her right in the law of equity as the beneficial owner.

Campaigning to change the legal position began in the 1850s, and eventually resulted in the Married Women’s Property Act 1870, which ‘allowed married women to be the legal owners of the money they earned and to inherit property’. With the Married Women’s Property Act 1882, ‘this principle was extended to all property, regardless of its source or the time of its acquisition’, and married women were recognised as legal entities in their own right. The intention of the Act is clearly stated at the outset:

1. (1) A married woman shall, in accordance with the provisions of this Act, be capable of acquiring, holding, and disposing by will or otherwise, of any real or personal property as her separate property, in the same manner as if she were a feme sole, without the intervention of any trustee.

Interestingly, the Married Women’s Property Act 1882 received Royal Assent on the same day as the Ancient Monuments Protection Act, 1882. The former confirmed that it would not ‘interfere with or affect any settlement or agreement for a settlement made or to be made, whether before or after marriage’, nor ‘interfere with or render inoperative any restriction against anticipation at present attached or to be hereafter attached to the enjoyment of any property or income by a woman’. The latter confirms that ‘a married woman entitled for her separate use, and not restrained from anticipation, shall for the purposes of this Act be treated as if she were not married’.

Conclusion

The Ancient Monuments Protection Act, 1882 is a widely-known piece of legislation, for its seminal role in the conservation of the historic environment in England. As noted by John Delafons (Politics and Preservation, 1997):

Here at once, as the result of one man’s work and practical administrative ability, were all the essential components of what later became Britain’s statutory system for the protection of ancient monuments.

But it is also a snapshot of wider society, with all its embedded assumptions and inequities. Within the context of the time, it is probably to be welcomed that explicit recognition was made for the rights of those monument owners who were married women, though it still makes uncomfortable reading. It would be fascinating to know, though, who the first such owner was.