Previous posts have looked at mechanisms other than the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England for identifying and protecting historic parks and gardens, most relating to other designated heritage assets (scheduled monuments, World Heritage Sites, listed buildings, and conservation areas). Of the remaining designated heritage assets, it is not surprising to see protected wreck sites omitted from this series, but registered battlefields are also missing, for good reason. This post explains why the designation is not directly useful in the protection of parks and gardens – though the links between the two are strong – and explores the world of registered battlefields.

Emergence

The story of the protection of battlefields begins with historic parks and gardens. The evolution of the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England is addressed here and here, and the way in which it is now used is outlined here. In essence, the National Heritage Act 1983 introduced a permissive power allowing what is now Historic England to create a Register of ‘gardens and other land situated in England and appearing to them to be of special historic interest’. A statutory consultation requirement was introduced in 1995, requiring local planning authorities considering planning applications for ‘development likely to affect’ registered parks and gardens to consult Historic England and the Gardens Trust (the former only in relation to Grade I and II* registered parks and gardens). Since 2010, national planning policy for the conservation of the historic environment has been the same for all types of ‘designated heritage asset’, including registered parks and gardens, and is predicated on the concept of ‘significance’ (defined as ‘the value of a heritage asset to this and future generations because of its heritage interest’).

In 1995, another register emerged: the England-wide Register of Historic Battlefields. This too is produced by Historic England (formerly English Heritage), and uses the same legal provision as the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England, namely the permissive power in the 1983 Act to create a register of ‘gardens and other land situated in England and appearing to them to be of special historic interest’. The Register of Historic Battlefields obviously makes more use of the ‘other land’ element of this provision, but, as with the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England, it is the requirement for that land to be regarded as having ‘special historic interest’ that does the heavy lifting here. Forty-three battlefields were added to the Register in the first year, and – as at May 2024 – there are forty-seven registered battlefields in total.

Battlefields (source: https://

www.battlefieldstrust.com/resource-centre/ periodpageview.asp?pageid=199)

Protections for Battlefields

As designated heritage assets, registered battlefields are subject to the same national planning policy as registered parks and gardens – as set out in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). They must be taken into account in preparing local plans, and are also a ‘material consideration’ in planning decisions (material considerations will be addressed in a future blog post, if you’re interested). Local planning authorities considering planning applications are required to give great weight to the conservation of registered battlefields – ‘great weight’ being the strongest in national planning policy. Any proposed harm to a registered battlefield requires ‘clear and convincing justification’, and substantial harm to registered battlefields should be ‘wholly exceptional’, to the point that local planning authorities should refuse consent where proposals would lead to substantial harm (unless that harm is necessary to achieve substantial public benefits that outweigh the harm or loss, or a range of specific tests is satisfied). As long as the planning system is invoked (not all proposals for change need planning permission), and the significance of the battlefield – and the impact of a development proposal upon it – is properly understood, this policy provides a strong degree of protection for registered battlefields.

The statutory consultation requirement for battlefield-related planning applications is the same as that for registered parks and gardens, with one exception. The Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015 requires that Historic England is notified of ‘development likely to affect any [registered] battlefield… of special historic interest’, but there is no requirement to consult the battlefields equivalent of the Gardens Trust, the Battlefields Trust, ‘a volunteer run registered charity dedicated to the protection, promotion and interpretation of Britain’s battlefields’. The Planning Practice Guidance does however note that:

Local planning authorities may also consult other organisations that they consider may have a particular interest in [a] proposed development. In this respect, local authorities may wish to consider consulting the Battlefields Trust in relation to applications affecting registered battlefields.

Improvements to protection are expected, however: section 102 of the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act 2023 introduced a form of statutory parity for ‘relevant’ designated heritage assets or their setting, to supplement the existing policy parity. Registered battlefields are identified as ‘relevant assets’, with the result that, when local planning authorities or the Secretary of State are considering granting planning permission for the development of land in England which affects a registered battlefield (or its setting), they will soon be required to have special regard to the desirability of preserving or enhancing that battlefield or its setting (section 102 is not yet in force). This includes preserving or enhancing any feature, quality or characteristic of the battlefield, or its setting, that contributes to its special historic interest. All of which should force more careful consideration of proposals, and improved conservation of battlefields.

The Register

Historic England describes the purpose of the Register as being to offer battlefields ‘protection through the planning system, and to promote a better understanding of their significance and public enjoyment’. A selection guide has been published to support the identification of battlefields for registration, but fundamental to designation is that:

If the site of a battle is to merit registration it has to have been an engagement of national significance, and to be capable of close definition on the ground. The most important factor will be the battle’s historic significance.

These ‘principal considerations’ – historical significance and location – are supplemented by ‘other considerations’, namely:

- Topographic integrity

- Archaeological potential

- Documentation

- Military innovations

- Biographic associations

- Commemoration.

The selection guide further confirms that ‘the scope of the Register has been limited to battles fought on land involving wholly or largely formed bodies of armed men, deployed and engaged on the field under formal command’. The original Register also identified five ‘Battle Sites’ – ‘further candidates for designation… for which there was insufficient evidence to allow the battlefield boundary to be drawn with any certainty’ – and eight (later nine) sites:

… where there had been significant engagements but where the battlefields no longer survived sufficiently intact to warrant designation or conservation measures, although there could be the potential for interpretation and presentation.

As outlined here, the registration process starts with a desktop study, then, if needed, a site visit. Further research follows, and the compilation of an initial report for consultation with the site owner, local planning authority, Battlefields Trust and the applicant, ahead of the production of the final recommendation report. ‘Where a battlefield is found to be of sufficient historic interest to merit registration, the site is deemed to be registered’, and the owners/occupiers and local planning authorities notified.

Once added to the Register, battlefields are not graded in the same way as registered parks and gardens or listed buildings: they are either registered or not. For those sites which are not registered, the selection guide notes that siege sites ‘are often already designated through listing and scheduling’, as sites of aerial or naval bombardment may also be. Other ‘sites of conflict’ may be identified on Historic Environment Records or local heritage lists.

The Battlefields Trust produces its own useful advice, including a policy on battlefield threats (primarily development, archaeological contamination, agricultural threats, and metal detecting), guidance on battlefield investigation, and a guide on managing change on historic battlefields.

Registered Battlefields

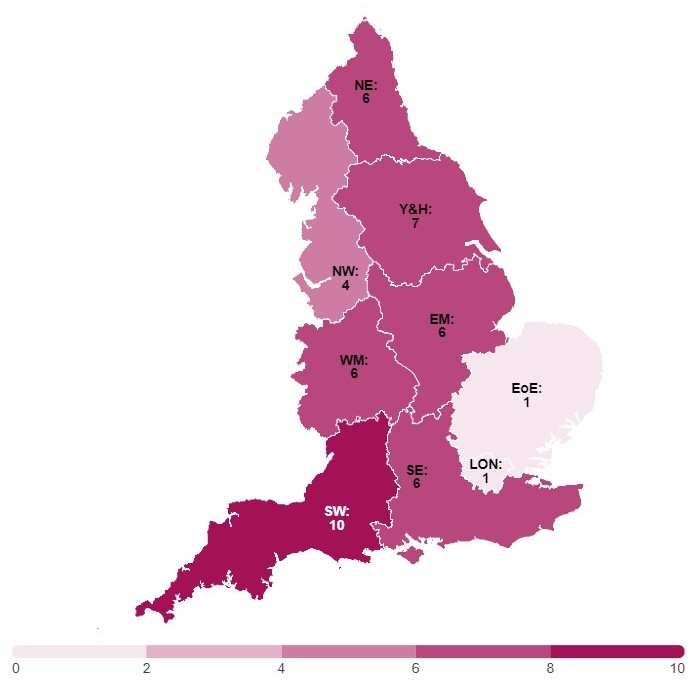

The 47 registered battlefields are spread across the country, with the largest proportion (21%) being in the south west, and the smallest (2% each) in the east and in London. Distribution across time also varies, with the battles commemorated dating from 991 (the Battle of Maldon, where the East Saxons faced the Vikings) to 1685 (the Battle of Sedgemoor, part of the Monmouth Rebellion, and ‘the last pitched battle to be fought on English soil’). Registered battlefields reflect some significant dates (such as 1066, and 1485), and some significant – and often protracted – events, such as the Wars of the Roses, and the Civil War (in relation to which, there are nine registered battlefields relating to 1643 alone).

Registered battlefields by government region,

December 2022 (source: https://historicengland.org.uk/research/heritage-counts/indicator-data/assets/)

Identifying battlefield sites is not always straightforward. As noted in the Battlefields Trust’s Battlefield Investigation: Policy and Guidance, ‘early modern battles are better recorded in primary sources than medieval ones and have more clues about where the battle was fought’. The Battlefields Trust sets out four phases for battlefield identification:

- Identifying the general location of the battlefield

- The collection and analysis of the primary accounts about the battle and relevant points from secondary works to understand what took place and to identify landscape clues in the accounts which might help place the action.

- The reconstruction of the historical terrain of the battlefield at the time it was fought so the landscape clues in the primary accounts can be used to develop a hypothesis about where the action took place.

- Testing the hypothesis systematically by surveying the proposed area using metal detectors to uncover evidence of the battle.

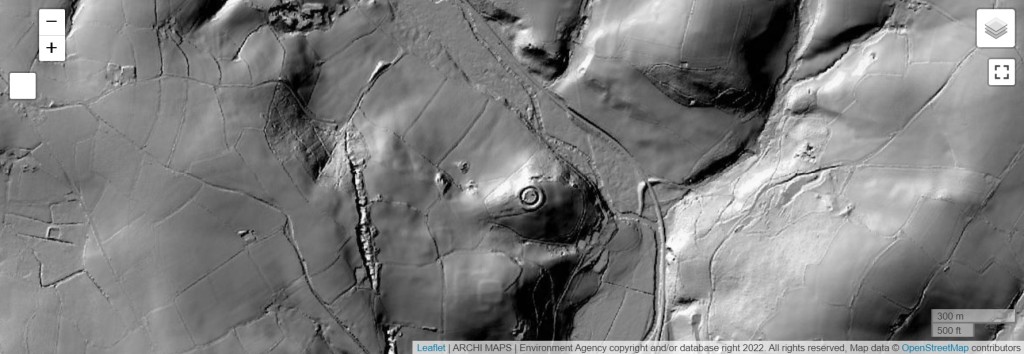

The challenges, and the value of thorough investigation, are well illustrated by the identification – and revision – of the site of the Battle of Bosworth (1485). In 2009, archaeological investigations confirmed that the original designation, and the location of the battlefield visitor centre, were inaccurate, with the battle actually having taken place some distance to the south west. The Register entry has since been amended to reflect the findings.

Battlefields and Parks and Gardens

Many registered battlefields also contain other designations. Listed buildings are most common, but some have scheduled monuments within their boundaries, such as the site of the Battle of Roundway Down (1643). Most excitingly, though, three registered battlefields overlap with registered parks and gardens.

The Battle of Hastings

The site of the Battle of Hastings (1066) coincides with the two discrete parts of the registered Battle Abbey landscape (Grade II). Battle Abbey itself was established by William the Conqueror in around 1070, with the altar located where King Harold fell. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Abbey and associated land were given to Sir Anthony Browne, who adapted the west range of buildings for residential use and demolished much of the rest. The site then changed hands over the years, becoming a school in 1922. The estate was however purchased for the nation in 1976, and remains in the guardianship of English Heritage.

The Register entry describes the gardens as ‘a monastic site with a few surviving features of C16 and C19 gardening activity, set within a C19 park laid out in and around the site of the Battle of Hastings’. The site of the Abbey church was transformed into a garden in the sixteenth century, and developed into a wild garden in the late nineteenth century. The Abbey’s cloister garden contained formal beds by the early nineteenth century (later changed to box-edged parterres), but is now lawn, in common with the sites of many other former garden features and Abbey structures within the garden. An exception is the surviving nineteenth-century walled garden. The park to the south of the Abbey remains open, and constitutes a major portion of the battlefield.

The Battle of Tewkesbury

The overlap between the site of the Battle of Tewkesbury (1471) and the registered landscape of Tewkesbury Cemetery (Grade II) is significantly less extensive. Edward IV’s victory on the battlefield marked the end of the second phase of the Wars of the Roses. The Register entry advises that, for the surviving portion of the battlefield, ‘the landscape character is much like that of 1471’, though the ‘core battle area to the east has been largely developed’.

The cemetery is surrounded by that development. It is a Burial Board cemetery, dating from the 1850s (and extended in the 1880s and 1930s), created in response to a burial crisis. The Register entry notes that it ‘survives largely intact’, with structural elements ‘of very good quality’, and that much of the original structural planting survives.

The Battle of Lostwithiel

The registered area for the Battle of Lostwithiel (21 August 1644) covers two discrete areas, the westernmost of which (centred on Restormel Castle) incorporates a portion of the Grade II*-registered Lanhydrock landscape.

According to the Register entry for the battlefield, the Lostwithiel campaign ‘culminated in the worst defeat suffered by a parliamentarian army’ during the Civil War. The Register entry’s assessment of the landscape is that it ‘survives very well with little major development’.

Only the southernmost portion of the Lanhydrock landscape lies within the registered battlefield, following the River Fowey to Restormel Castle (the focal point of a picturesque view), and connected by a drive, ‘today surviving in part as a footpath and in part as a public road’ – this drive was in place by 1813, accompanied by ornamental planting.

The current house at Lanhydrock has seventeenth-century origins, and was rebuilt in the 1880s after a fire. The property (which was passed to the National Trust in 1953) is described in the Register entry as:

Gardens of mid C17 origin which were further developed in the C19 and C20, together with a mid C17 deer park which was extensively landscaped in the early and mid C19.

What does all this mean for the protection of these registered assets? Arguably, the slightly greater consultation requirements for parks and gardens mean that garden designations are more likely to benefit battlefields, rather than the other way round. The detail of the ‘special historic interest’ will differ between the two, though, so, despite the use of the same legislative provision, there is still a distinction to be drawn between the two designations in practice.

Conclusion

Registered battlefields have much in common with registered parks and gardens, including a desire for their stronger protection, as observed here. One quality they hold alone, though, is the ‘honour’ of being the last of the heritage designations in England, after their emergence in 1995 – over a hundred years after the introduction of scheduling, and over ten years after the introduction of the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England.